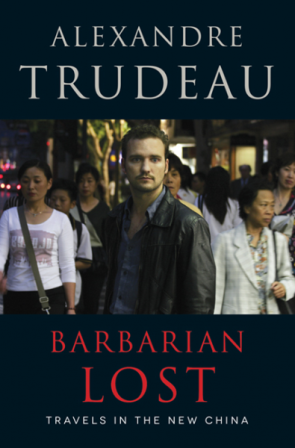

Barbarian Found

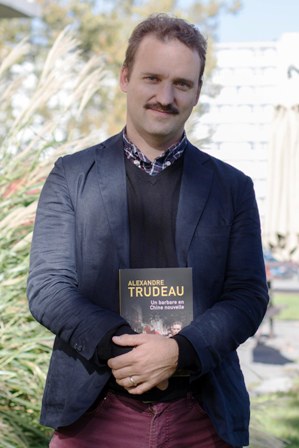

As a child, travelling with his father – former Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau – Alexander Trudeau was captivated by China’s immensity, intimacy and intricacies. Recently, the documentary filmmaker-turned-author returned to the ‘Sleeping Dragon’, only to find it very much awake.

As a child, travelling with his father – former Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau – Alexander Trudeau was captivated by China’s immensity, intimacy and intricacies. Recently, the documentary filmmaker-turned-author returned to the ‘Sleeping Dragon’, only to find it very much awake.

CL: Let’s start with your family history here – you have Celtic roots do you not?

AT: Yes, both of my parents have Scottish ancestry. On my father’s side there are the Elliots, and on my mother’s side there are the Sinclairs.

CL: Does that heritage impact who you are today?

AT: Yes, it does, very much so, as I think it does for a lot of Canadians. The Scots are fiercely proud of their roots, and I count myself among that group. Our ancestors were really at the forefront of building this country, with their spirit of adventure and sense of bravery. My great-grandfather, on my mother’s side, emigrated here with his family and became a schoolteacher. He was also, apparently, a very good storyteller.

CL: The Scots have always excelled at spinning a good yarn.

AT: Yes, that’s a big part of my heritage, for sure. For a long time I thought of myself more as a story liver, however my need to carve out a profession has turned me into a storyteller of sorts, first through filmmaking and now with the book.

CL: Let’s talk about that story then. What motivated you to write Barbarian Lost?

AT: There were a number of motivations at play. The first was quite a simple one actually; I was asked to write a short preface to a re-edition of my father’s book on China, and the publisher (Douglas & McIntyre) saw that I could write and had a lot to say about the country. So they asked me to consider putting together a full book of my own on the subject. I said yes, mostly because I was driven by my own need to make some sense out of China; I have been watching it from afar since that first trip there with my father in 1990, and I have been witness to its emergence as a dominant world power. I’m a bit of a geo-political junkie, so understanding how the world works is intricately interwoven with better understanding the complexities of China and its role on the global stage.

C L: You often use the image of a river in the book to describe China.

L: You often use the image of a river in the book to describe China.

AT: I’m not sure that I intended to do that, but in hindsight I can appreciate the symbolism. It is important to understand that China is not a country; it is a civilization – perhaps even a way of life. And while that civilization is ancient, and has appeared almost stoic and static like a river for thousands of years, more and more we are seeing that it is actually quite fluid and dynamic as it flows into the sea of global influence. The other misperception we have is that there is one China; China today, or at least my China, is made up of many different peoples. Sometimes they speak in harmony, while at other times they are a mass of contradiction. And that is part of the complexity that I undertake to detail in the book. And with China, you can’t travel there without coming under the spell of the ebb and flow of the Tao; the spinning of the eternal wheel that is China’s story, with great periods of alternating darkness and light.

CL: The journey seemed an internal one for you, as much as it was a physical voyage.

AT: All journeys are. One travels, first and foremost, in a mental way. Travel is a frame of mind, where we can let go of what we know, and visit places that are unknown.

CL: Is that the difference between being a tourist and being a traveler?

AT: Yes, perhaps. A tourist rarely leaves their comfort zone, whereas the traveler leaves one’s preconceived notions behind and doesn’t look back. A tourist is packaged with a plan, and becomes alarmed when that schedule is disrupted, whereas a traveler puts oneself at the mercy of a place and a people, in a good way, where those things will dictate the agenda.

CL: It appears that you went out of your way in China to be a traveler.

AT: I wouldn’t know how to be a tourist. I’ve never been that interested in sightseeing, unless I stumble upon something by accident. To really understand a place and people, like China, it means going beyond and behind what it is trying to show you, or what is propped up. Actual meaning is found in the nitty-gritty, the daily heartbeat, which often means going off the beaten track – like being in people’s homes, and essentially being where they are.

CL: The soul of China’s people, and even its landscape, reveals itself in the book.

CL: The soul of China’s people, and even its landscape, reveals itself in the book.

AT: Again, I’m not sure that was intentional. It is challenging to capture something so intangible, so instead of making these grand statements about the spirit, I aimed for a collage of sorts – snapshots of individual people and places, with the hope that a bigger picture would emerge from that. Ultimately, the soul of China is the Tao; the rhythm of that ever-spinning wheel. That rhythm is not something that is easy to see sometimes; it’s not always logical, and I’m not sure that the Chinese people are always aware of it because they are in the middle of it. In fact, many of them are quite surprised by what is happening to their country. However, there were small hints of it, glimmers here and there that showed themselves to me during my travels.

CL: How is writing a book different from filmmaking?

AT: From a practical perspective, filmmaking is a much smaller palate to work with; I have an hour to say what I have to say. Whereas, with the book, I had this huge, empty canvas to fill in over a much longer period. And where filmmaking invites dialogue and the participation of others, long-form writing is a solitary act. I used to think that all you needed to write a book was mental aptitude – big ideas and sheer brain power. Now I understand that it requires bravery above all else. It takes great courage and endurance to sit before a blank page each day and go to work. I have even more respect and admiration for writers after going the distance with my own book.

CL: Did you accomplish what you set out to accomplish with the work?

AT: That is really for others to decide. Does the reader get a strong feeling for China? Do they become fascinated with the country? In that sense, my goal was to write something that was both light and deep at once – that was easy and accessible to read and yet carries some weight as well. Will people get a better understanding of how China works after reading it? Time will tell I suppose. I hope so. But, yes, I feel good about the book.

CL: What has the response been like from the people around you?

AT: I think they all appreciate it. Some of them are surprised, perhaps, by how easy it is to read, and some of the light-hearted humour. They think I am this very serious and complicated guy. And, given how private and reclusive I have been at times in the past, some were surprised at how candid I was, and how much of myself I put out there in terms of my failures, my mistakes, and so forth.

CL: Now that you have written a book, will there be others?

CL: Now that you have written a book, will there be others?

AT: As I said earlier, I’ve always considered myself a story liver. However, storytelling is a way to keep living those stories. There may have been multiple trips to China, but then there was this completely other journey that took place in my mind as I was writing the book. That process revealed many things about China that I hadn’t considered while I was there. And being a man of many interests – film, geo-politics, journalism, art – I really enjoyed writing. And there is something about travel writing that is so immediate and honest and natural – I went there, I saw this, I did that – that it is very rewarding as a storyteller. So, all that said, I am revisiting some of my old travel journals looking for opportunities.

CL: You’ve been quite pro-active with art – have you considered politics?

AT: I’m more of an intellectual and a lone wolf than an activist. I’ve stood up for social justice in this country, and will continue to do so, but activism is something I mostly admire from afar. I guess that I also have a difficult relationship with political action; I feel that it gets in the way of pursuing ideas. I certainly have ideas about how the world should be, but I’d rather find that voice in my art that in any political arena. And now that I am a father myself, I need to think about how I live my life every day and what kind of example I am setting for my own children.