Moat Brae

Standing behind the red sandstone, Georgian villa – once known as Number One, Dumfries – the lawn is spread out in front of me, passing between several large trees before sloping down to the gentle, flowing waters of the River Nith. A sudden gust of wind sent a column of leaves spiraling upwards, and the tall trees whispered in the breeze. Nearby, I heard the tinkling of a bell followed by the sound of children escaping the clutches of school. Filled with excitement I trod cautiously for this was a very special place – I was in the garden where Peter Pan was born.

Standing behind the red sandstone, Georgian villa – once known as Number One, Dumfries – the lawn is spread out in front of me, passing between several large trees before sloping down to the gentle, flowing waters of the River Nith. A sudden gust of wind sent a column of leaves spiraling upwards, and the tall trees whispered in the breeze. Nearby, I heard the tinkling of a bell followed by the sound of children escaping the clutches of school. Filled with excitement I trod cautiously for this was a very special place – I was in the garden where Peter Pan was born.

Ever since J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan – or, The Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up – debuted on stage in London in December of 1904, various film and pantomime adaptations of the original story have ensured its place as a Christmas favourite. In 1911, Barrie published the novel Peter and Wendy, and the boy who could fly soon winged his way around the world. But few people are aware that the story that has gripped the imagination of children and adults alike began in the garden of Number One, Dumfries – now known as Moat Brae.

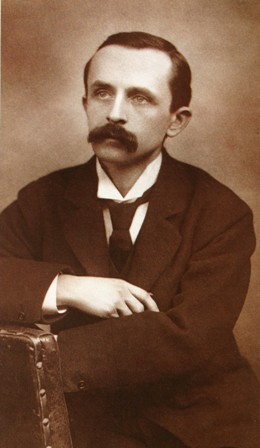

James Matthew Barrie was born on May 9, 1860, in the small Scottish town of Kirriemuir. He was the ninth of ten children born to David Barrie and Margaret Ogilvy. When Barrie was six years old his elder brother David died in a skating accident. The young Barrie did everything he could to comfort his distraught mother – even wearing his brother’s clothes and emulating his whistling – but her greatest comfort, and one that made a lasting impact on Barrie, was her belief that because her son had died young he would never grow up and leave her.

In 1873, at the age of 13, Barrie was living in Dumfries with his older brother Alexander and his sister Mary Ann. The house they occupied was next to Dumfries Academy, where Barrie was enrolled as a pupil, and only a short walk from the impressive Moat Brae, home of his school friends Stuart and Hal Gordon. Together the three boys would let their imaginations run wild in the grounds of Moat Brae and enact swashbuckling pirate adventures along the river. Many years later, Barrie acknowledged that; “When I came to the Academy I intended to work hard – and I would have probably worked hard – had it not been for another boy who led me astray. It was Stuart Gordon. But that wasn’t the name he was known by at school. He came up to me and asked my name. I told him. That didn’t seem to please him. He said; I’ll call you Sixteen String Jack. I asked his name and he said it was Dare Devil Dick. He asked me if I would join his pirate crew. I did. That was fatal to my prize giving.”

Barrie spent many happy hours playing in Moat Brae, its garden and the adjacent banks of the River Nith leading him to note, “I was more in that house than any other in Dumfries.”

Barrie spent many happy hours playing in Moat Brae, its garden and the adjacent banks of the River Nith leading him to note, “I was more in that house than any other in Dumfries.”

During Barrie’s five years in Dumfries, the town’s Theatre Royal, one of the oldest working theatres in Scotland, underwent a major renovation by renowned theatre architect C. J. Phipps. As a regular visitor to the theatre, the new state of the art facilities – and the exciting, visiting productions that the theatre attracted – must have made an impression upon him. Also, at that time Dumfries was able to boast one of only two camera obscuras in Scotland. It is almost certain that the inquisitive Barrie and his two friends would have visited such an unusual and exciting attraction to experience the wonderment of seeing an aerial view of Dumfries projected on the circular surface before them – one that created a sense of flying! Barrie must have been impressed by the amazing experience of a camera obscura, for years later he gifted a cricket pavilion complete with camera obscura to his hometown of Kirriemuir.

Adding all of these influences together, it is not difficult to see how they fuelled the imagination of a young boy playing in the enchanted garden of Moat Brae. In 1906 the Gordons sold the house to a knitwear manufacturer, and from 1914 until 1997 it was a nursing home. It was then purchased by a businessman, who planned to create a themed hotel, but the project never materialized and it was sold to a local Housing Association. A lack of funds and maintenance over the years took their toll, and by 2009 the house was in a perilous condition. With the roof in danger of imminent collapse, the Housing Association decided to demolish the building and clear the site. To lose such an important part of the town’s – and nation’s – history was anathema to some of the local townsfolk and so they formed the Peter Pan Action Group. With only three days left until the bulldozers moved in they obtained a court injunction to prevent the demolition of the inspirational property. The Peter Pan Moat Brae Trust was then formed and was granted three years to accrue the £75,000 necessary to buy the property from the Housing Association, or it would again face demolition. Just in time, the necessary funds were raised. Having saved the property, however, the dilemma was now what to do with it.

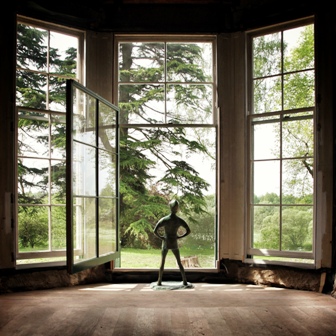

The first priority was to halt the on-going decay of the building, and sufficient funds were raised for essential building works to render it wind and watertight. Inside its spacious interior, fragments of the original décor remain. Remnants of ornate, crumbling cornices, mosaic floors, and huge windows overlooking the garden provide a glimpse of the world that Barrie frequented as a boy. It was a world of imagination, and it is imagination that is the key to the future of Moat Brae.

The first priority was to halt the on-going decay of the building, and sufficient funds were raised for essential building works to render it wind and watertight. Inside its spacious interior, fragments of the original décor remain. Remnants of ornate, crumbling cornices, mosaic floors, and huge windows overlooking the garden provide a glimpse of the world that Barrie frequented as a boy. It was a world of imagination, and it is imagination that is the key to the future of Moat Brae.

In March 2011, Cathy Agnew, project director for PPMBT, was delivering a paper on Moat Brae to the International Conference, ‘A Hundred Years of Peter Pan and Wendy’ hosted by the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Spain. She recalls, “I was talking with the other delegates and became aware of their immense interest and enthusiasm for the place that nurtured Barrie’s imagination.”

“In an instant I realized that what was special about Moat Brae House and its garden was that it was a place of inspiration and that it should continue to inspire future generations.”

From this epiphany emerged a clear direction for the restoration of Moat Brae.

Back in Dumfries, and with the assistance of renowned actress Joanna Lumley as patron, the plan was launched for Moat Brae to become the National Centre for Children’s Literature and Storytelling, inspiring future generations of children and adults alike to harness the power of imagination. Since then, over £5M has been raised.

In 2017, a new curtain will rise at Moat Brae, Dumfries, as construction work will commence on site. The National Centre for Children’s Literature and Storytelling will accommodate writers and artists in residence, with new spaces for all types of creative arts including writing, drawing, acting, filming and playing, with a family reading room, an education suite, a café, a bookshop and more. And, of course, it will have its own enchanted Neverland Garden with adventure trails, art installations, performance spaces and places to explore – all overlooking the river where Barrie and the Gordon brothers acted out their pirate adventures. In Barrie’s words it would seem that, “Dreams do come true if only we wish hard enough.”

There is still much work to do to complete the designs and raise the funds for the interior installations that will follow once the main construction works are complete. Unfazed, the Peter Pan Moat Brae Trust has already shown the true power and magic of imagination – the same power of imagination that Barrie noted in a 1924 speech when he was granted the Freedom of Dumfries, “When shades of light began to fall, certain young mathematicians shed their triangles and crept up trees and down walls in an odyssey which would long after become the play of Peter Pan. For our escapades in a certain Dumfries garden, which is enchanted land to me, were certainly the genesis of that nefarious work.”

www.peterpanmoatbrae.org

www.tomlanglandsphotography.com