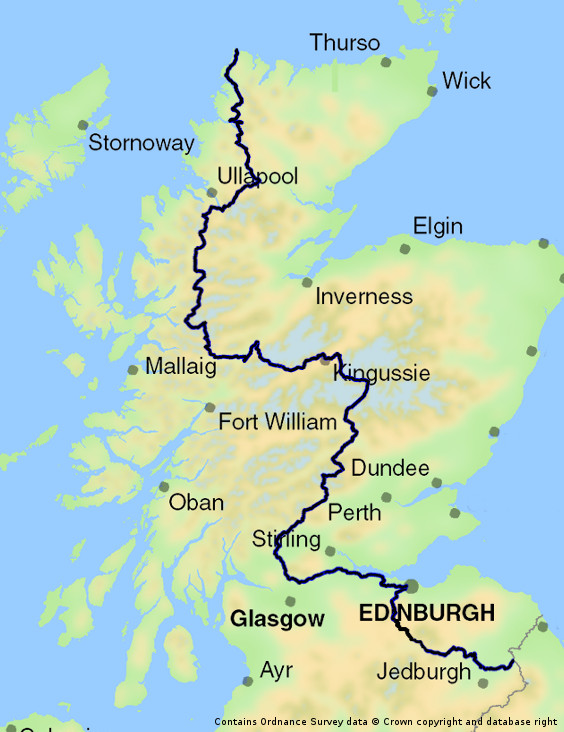

The Scottish National Trail is an 864-kilometre-long walking route running the length of Scotland from Kirk Yetholm to Cape Wrath. Co-founder Cameron McNeish tells us more.

The Border Hotel in Kirk Yetholm is well known to long distance walkers. It’s there many of them collapse into the bar after walking 354km from Edale in Derbyshire along the Pennine Way, the spine of England. But, recently, I left the hotel and headed off in the opposite direction. My own walking odyssey was about to begin – 757km through the length of Scotland to Cape Wrath, the most north-western point on the Scottish mainland.

But why undertake a challenge like this – five weeks walking through all kinds of weather and landscapes? Well, in the course of a 757km walk through a country you get the opportunity to observe things at closer quarters than you would if you were to drive through it. Travelling by foot takes you into wild landscapes that most people are totally unfamiliar with. And I wanted to discover a little more about my own land, at a time when so many of us are questioning our national identity. My long route, created ostensibly for two BBC television programs that were broadcast last December, can be broken down into four sections: this southern section between Kirk Yetholm and Edinburgh; a route between

Edinburgh and Milngavie following the Union and Forth and Clyde Canals; a central Highlands section between Milngavie and Kingussie; and the final haul between Badenoch and Cape Wrath. I decided to call it the Scottish National Trail. Kirk Yetholm is also on the route of the St. Cuthbert’s Way, a 100km route that follows in the footsteps of Cuthbert, a seventh century priest who became the Prior of the Celtic monastery at Melrose. The route runs from Melrose Abbey to Lindisfarne in Northumberland and since I was heading for Melrose it seemed a little churlish not to follow in the footsteps of the saint.

The St. Cuthbert’s Way was the first of several established routes that I followed in the course of the Scottish National Trail. From Melrose, I would take the Southern Upland Way to Traquair and from there a series of Tweed Trails took me to Peebles and beyond, over the Meldon hills to West Linton where a series of Pentland Trails took me all the way to Balerno on the outskirts of Edinburgh.

A footpath alongside the surprisingly lovely Water of Leith took me into Edinburgh and the start of the Union Canal. I felt fairly strongly that you couldn’t call a route the Scottish National Trail and not visit our capital city!

The towpaths along the Union Canal and then the Forth and Clyde Canal were one of the surprises of the walk for me. Like a green artery running right through the Central Belt of Scotland these canals are well looked after by Scottish Canals and I shared the towpaths with walkers, cyclists, joggers and dog walkers.

Beyond Cadder, on the outskirts of Glasgow, I followed tracks and minor roads to Milngavie and the start of the popular West Highland Way. The route was busy and I was glad to leave it at Drymen to follow the much quieter Rob Roy Way to Aberfoyle then over the Mentieth Hills to Callander, in the very heart of the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park. I left the Rob Roy Way for a while and followed rights of way through Glen Artney and Glen Almond, which took me to Tayside and Aberfeldy where I met up with the Rob Roy Way again. I followed it to its finish in Pitlochry.

Shortly after that, came the remotest part of the walk so far – through the Cairngorms National Park by Glen Tilt, Glen Geldie, Glen Feshie to Kingussie, then by Laggan to the Corrieyarack Pass and over the Monadh Liath hills to Fort Augustas.

More canal towpaths, this time following the Caledonian Canal, led me to Glengarry where a day’s forest walking took me to the start of the finest section of the whole route. Thus began a long, tough trek through some of the most majestic, remote and stunningly beautiful landscape you could dare imagine.

There are no official long-distance footpaths through these northern hills although a notional Cape Wrath Trail, from Fort William to Cape Wrath, offers several alternative and unsigned routes. I had given myself several rough guidelines for this long section: the route should follow a south to north line as close as possible; it should allow passage through the most scenic areas; it should try and avoid tarmac and paved roads or paths but instead follow existing footpaths and stalkers’ tracks as much as possible and it should avoid crossing mountain ranges and major rivers except where necessary. The resultant route is a stunner, without doubt the finest long distance walking route in the land. But it’s not for the inexperienced. There are rivers to cross and passes to climb; there are sections where navigational skills could be crucial, particularly in bad weather, and accommodation is scarce. You couldn’t find anything more different from the rolling hills of the Borders.

The route snakes through the Northwest Highlands and the kind of places that thrum the heartstrings of hill-walkers everywhere – Kintail, Torridon, An Teallach, Glen Oykel, Assynt and then, as a wonderful finale, along the wild coast from magical Sandwood Bay to Cape Wrath lighthouse, the end of the route and the end of Scotland. Beyond lie the glistening northern seas… Next landfall is the Faroes.

Throughout the walk, I often sat beside some long-ruined shieling (a house or hut) and thought of the people who once lived and worked in these glens, many of whom were later evicted. Large scale sheep farming replaced people after the Highland Clearances and today those sheep have largely gone. Victorian sporting estates dominate the Highlands and large areas of the Borders and one wonders how sustainable they are in these uncertain times. Very few of these estates are profitable and many landowners keep them on as hobbies, as playthings. While some land managers are working hard to regenerate native woodland and control deer numbers most estates are run on a monoculture basis, managing vast acres as a wet desert for a few grouse, or encouraging large numbers of red deer, which browse every bit of new vegetation that pokes its head out of the dirt. This is surely not the way ahead for Scotland? Land reform is one answer, where communities control the land on which they live and work, and there have been some success stories like in Knoydart, Assynt and the Isle of Eigg, but large-scale community buy-outs are still a long way off, particularly under the current economic climate.

Throughout the walk, I often sat beside some long-ruined shieling (a house or hut) and thought of the people who once lived and worked in these glens, many of whom were later evicted. Large scale sheep farming replaced people after the Highland Clearances and today those sheep have largely gone. Victorian sporting estates dominate the Highlands and large areas of the Borders and one wonders how sustainable they are in these uncertain times. Very few of these estates are profitable and many landowners keep them on as hobbies, as playthings. While some land managers are working hard to regenerate native woodland and control deer numbers most estates are run on a monoculture basis, managing vast acres as a wet desert for a few grouse, or encouraging large numbers of red deer, which browse every bit of new vegetation that pokes its head out of the dirt. This is surely not the way ahead for Scotland? Land reform is one answer, where communities control the land on which they live and work, and there have been some success stories like in Knoydart, Assynt and the Isle of Eigg, but large-scale community buy-outs are still a long way off, particularly under the current economic climate.

So what’s the next throw of the dice for Scotland’s wild places? I wish I knew. My end-to-end walk threw up lots of questions, but few answers. Renewable energy appears to be the most obvious bet and that isn’t a pleasant option for those of us who treasure the wild places, unless we can find a means of balancing our energy and climate change needs with landscape conservation.

I’ve probably enjoyed the best of Scotland’s wild places in my lifetime, but I have grandchildren and I want the best for them too. I want them to enjoy Scotland’s hills and glens as I have because I know the benefits of such a relationship. Those of us who love wild land have a duty to speak up for it, to fight for it. But first take the bus to Kirk Yetholm, tie up your boot laces, hoist your pack on your shoulder and gaze north. Lying before you is an adventure like no other. Step out and enjoy it before things change too much. A nation awaits you…

www.scottishnationaltrail.org.uk

Leave a Comment