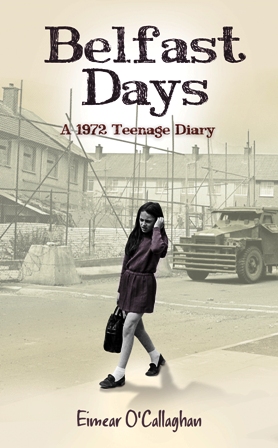

BELFAST DAYS

The teenage years can be troubling no matter where one grows up. For journalist and author Eimear O’Callaghan, coming of age in Belfast in the early 1970s brought more than its share of Troubles. Recently we spoke with her about her first book, Belfast Days.

The teenage years can be troubling no matter where one grows up. For journalist and author Eimear O’Callaghan, coming of age in Belfast in the early 1970s brought more than its share of Troubles. Recently we spoke with her about her first book, Belfast Days.

What are your own roots?

I was born into a very ordinary, happy, Catholic family in nationalist West Belfast — the eldest of five children and an only daughter. Andersonstown, where I was reared, was — and still is — a hug, sprawling, and predominantly nationalist district of the city. Because of Belfast’s segregated, divided and troubled nature in the 60s and 70s, I grew up without knowing a single Protestant until I went to university. My parents, relatives and neighbours were all Catholics as were my friends and teachers at the school I attended, St Dominic’s Grammar School on the Falls Road.

What inspired you to become a writer?

My father, Jim, instilled in me, from an early age, a passion for the written word; reading to me when I wasn’t old enough to do so myself, reciting his favourite poems, sharing his love of literature and encouraging me to read newspapers. I also inherited from him an abiding interest in news and current affairs. I began to devour books as soon as I could read but as a teenager, I was more of a reader than a writer. It was only when I was studying at Queen’s University, and violence and mayhem convulsed Northern Ireland, that I knew journalism was the career I wanted. Now, looking back at the diary I wrote when I was 16 — and seeing my precocious obsession with the North’s deteriorating political and security situation— it’s obvious I was destined to be a journalist. I just didn’t realize it at that time.

Are they the same reasons you do it today?

Since leaving my job at the BBC five years ago, I’ve taken a step back from news journalism to concentrate instead on feature writing and more recently, on my first book, Belfast Days. But the motivation is still the same: to share a story, paint pictures, stimulate debate, challenge old ideas and encourage fresh thinking.

How have you grown as a writer over time?

I regard them as two distinct phases in my working life. I began my newspaper career as an absolute greenhorn — having never set foot in a courtroom or a council chamber, let alone report from the scene of shooting or an explosion. It was initially daunting but tremendously exciting. Transferring to radio and television broadcasting in Dublin a few years later brought new challenges — more advanced technology, tighter deadlines, working with the spoken rather than the written word, and the thrilling adrenalin rush of live broadcasting. That broadcasting buzz sustained me through nearly two decades at the BBC before I moved into editorial management: shaping output, molding staff and balancing budgets. Throughout my career, though, a voice urged me to write a book and refused to be silenced. Now, freed from the relentless pressure of broadcasting deadlines, and armed with knowledge and confidence garnered over decades, I can indulge my love of the written word without the restraints of journalistic objectivity and impartiality.

What motivated you to write Belfast Days?

Finding my 1972 teenage diary and reading it for the first time in nearly 40 years set in motion a train of events that eventually compelled me to write Belfast Days. The book, which I certainly hadn’t planned, took on a life of its own after I submitted a feature to The Irish Times based on a short excerpt from the diary. That extract recorded my shocked, heartbroken schoolgirl reaction to the events of Bloody Sunday when British soldiers shot dead 13 innocent civilians taking part in an anti-internment march in Derry. The paper printed my article on June 15, 2010 — the day the British Prime Minister David Cameron apologized for the killings, declaring them to be ‘unjustified and unjustifiable’. I was amazed by the response that the newspaper article and subsequent radio interviews elicited at home and as far away as the west coast of America. Complete strangers, including a radio producer and a writer in Seattle, urged me to publish the diary. I gradually realized that I had a story to tell about what ‘ordinary’ everyday life was like for an unexceptional Catholic schoolgirl and her family in 1972 — the worst year of the Troubles — when almost 500 people were killed. Making the decision to proceed with the book wasn’t easy. The diary’s contents were often harrowing, shocking, disturbing and uncomfortable for me to read. It was also funny and embarrassing at times, with its recollections of the rough-and-tumble of ordinary family life and flashes of my teenage tantrums and angst. I’m a very private person by nature, and I never intended my diary to be seen by eyes other than my own. I was nervous about sharing my innermost dreams, fears and prejudices and was also apprehensive about how I might be perceived by people not only within my own community but within the unionist community as well. Ultimately, though, I decided I’d no choice but to write the book — even if only for my own children. I wanted to remind people, at home and abroad, how much we have forgotten; to show how easily two god-fearing communities plummeted to near civil war; to warn against the danger of taking the current peace in Northern Ireland for granted, and to celebrate the better place we’re in today.

What did you learn during the process?

I learned more than anything that time doesn’t necessarily heal but it certainly blurs details and softens pain. I appreciated for the first time the resilience of ‘ordinary’ people — men and women like my parents — who struggled in the most difficult, life-threatening circumstances to preserve family life. And I realized how easily adults and young people in situations of conflict — schoolchildren like me — can become inured to violence and death. I learned too that if Northern Ireland is to deal effectively with its tragic past, people must be encouraged to share their individual stories; more importantly, we must all be prepared to listen to them.

How did you feel when the book was completed?

I found it very difficult to let go and were it not for the publisher’s deadlines, I’d probably still be re-writing every line and paragraph; in that sense, ‘completion’ was an anticlimax. By contrast, the excitement of having a brown cardboard box, carrying the first copies of Belfast Days, delivered to my door was comparable only to seeing my newborn children for the first time. Quite by chance, my husband Paul was at home when the postman called and was there to witness me ripping off the sealing tape, scattering the protective packaging and holding and smelling my ‘real’ book for the first time. As a feeling of completion, achievement and pride engulfed me, tears weren’t far away.

What has the response been like so far from those that have read it?

It’s been overwhelmingly positive. Reviewers have praised the insight the book provides and, more importantly, my honesty and fair-mindedness. Readers in Britain and in the Republic, as well as many young people, have told me they’d “no idea what it was like”. On a personal level, Belfast Days has re-ignited friendships with girls I haven’t seen or spoken to since we were at school 40 years ago. Many of them, as well as total strangers, have got in touch to thank me for writing about that time — for evoking a mixture of happy and sad times, including memories they’d unconsciously buried. What’s been most gratifying for me is the response from members of the Protestant and unionist community who’ve spoken about what they’ve learned from Belfast Days — both about themselves, and also about the nationalist experience of the Troubles. Strangers have tracked me down via the internet — have even called to my door — to talk about the light it has thrown on our shared past and the views it has challenged. The Sinn Fein President, Gerry Adams, generously described the book as an “insightful, evocative and important reminder of teenage days in war-torn Belfast.”At the opposite end of the political spectrum, a former leader of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland urged his congregations to “read this diary. In the process you may smile, you may be shocked, you may even see your own reflection.” Such responses are immensely humbling.

What did your family think of the book?

The book churned up a lot of memories, happy and sad, for my mother and my four brothers who all still live in Belfast. It introduced my son and two daughters to a violent and unrecognizable past — in the city where they’ve recently studied, worked and socialized — that both shocked and disturbed them. But without exception, they’re all extremely proud. Unfortunately, my father didn’t live long enough to see my book published but I know that he, as someone who always dreamed of writing a book about the North, would have been equally proud.

What makes a good book?

Empathetic characters and lyrical writing. A good plot or story line helps but for me it isn’t essential. Give me a writer whose love of words is immediately obvious, who introduces me to fully formed, three dimensional characters and I’ll happily immerse myself in his or her book. I love books that explore the workings of the psyche as it deals with the darker but ever present aspects of life – change, loneliness, exclusion, ageing and loss.

What are your thoughts on the state of Irish literature today?

It’s going through the most exciting phase that I’ve ever witnessed – almost a renaissance. Ireland is changing and the old ‘dependables’ – the religious, political and financial institutions – are being shaken to their foundations; it experienced unparalleled growth during the Celtic Tiger era and then wilted under an economic recession. While all this was happening — and possibly because of it —there’s been a great burst of literary activity with exciting writers, young and old, coming to the fore, including people like Colm Toibin, Sebastian Barry, Emma Donoghue, David Park, Colum McCann, Eimear McBride and my latest discovery, Sara Baume.

Have you read other literary efforts about the Troubles?

I don’t seek out books about the Troubles. Too many of them feed into the propaganda of one side or the other, even though the writer mightn’t consciously have set out to do so. Others fictionalize and glamourize what was a dark, painful period in our very recent history. I prefer to give such books a wide berth.

What’s next on your creative agenda?

Since rediscovering my teenage diary and delving into its pages, I’ve been fascinated by the idea of memory: what we remember and, more importantly, how we remember. I’d love to have a go at fiction next, building on what I’ve learnt about how the passage of time softens, blurs, distorts and even obliterates events from our pasts. It’s still very much at the exploratory stage but who knows what the coming months might bring.

www.facebook.com/eimear.ocallaghan.9

Leave a Comment