Che’s Celtic Connection

Jim Fitzpatrick, the artist who created the iconic Che Guevera image known around the world, is sticking to his pacifist principals as he awaits the legal transfer of his artwork to Cuba. Here he tells Donald Wiedman why.

Jim Fitzpatrick, the artist who created the iconic Che Guevera image known around the world, is sticking to his pacifist principals as he awaits the legal transfer of his artwork to Cuba. Here he tells Donald Wiedman why.

In today’s world where hundreds of people are ‘famous just for being famous’, Dublin resident and Celtic Art master draftsman Jim Fitzpatrick is perhaps the exact opposite.

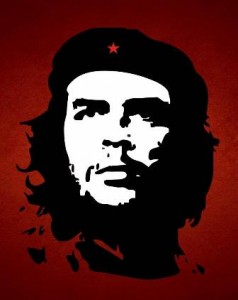

Fitzpatrick is, and has been since 1968, the unknown Irish artist behind the famous, un-copyrighted, widely reproduced – and now truly iconic – red and black Che Guevara poster, and the millions of lookalike t-shirts, murals, accessories and tattoos since.

Fitzpatrick’s artwork, based on a photo by then unknown Cuban photographer Alberto Korda, was creatively spurred on by his own youthful outrage over the death of his revolutionary hero in October 1967. Hand drawn – with Che’s eyes altered to look slightly upwards, and a jagged ‘F’ for Fitzpatrick tucked into the lower right hand corner – Fitzpatrick’s artistic inspiration also came from his Irish Catholic education.

“My ‘ideas’ come from a lot of different sources,” he said, “but my ‘ideals’ I was given by my educators. I went to a Catholic school, and the Franciscans who educated me taught long lessons on injustice in Latin America. It was Father Leonardo Boff of Brazil, the Franciscan, who came up with ‘Liberation Theology’ – a most revolutionary concept.

“Being a Catholic Christian, I take the teachings of Jesus, and apply them in a revolutionary way,” Fitzpatrick explained, believing that if Che had been a Christian, he would have followed the same ideals. “Of course he wasn’t. But if you’re dealing with a brutal regime like the Batista regime, pacifism will get you nowhere. I just stick to pacifist principals if I can, so I disagree with Che on certain things.”

Fitzpatrick once briefly crossed paths with the famous Guevara, in 1963 when Fitzpatrick was 15 and working in a hotel in Kilkee, County Clare. With Che’s plane grounded by fog during a refueling, Fitzpatrick recounted, “Che and his entourage came into the pub I was working in. I came from a very ‘lefty’ political family, so it was no surprise to me that I recognized him immediately – though he was surprised that I recognized him.

“You don’t see very many tough-looking, Latin cowboy types – but that’s what they reminded me of. There were swing doors in the hotel, and they just walked in like they were walking into a Wild West saloon. They had this very militaristic look about them, but they were very amiable, very funny.”

Fitzpatrick remembered Che’s English as excellent. “Really the essence of our brief conversation was that he was very proud to be Irish, and have Irish blood.” Che’s paternal grandmother was Ana Lynch, a descendent of the Lynch family from Galway. Family head Patrick Lynch immigrated to Buenos Aries in the mid-1800s. “Which amazed me,” Fitzpatrick exclaimed, “I’d never heard of that!”

After Che’s murder in Bolivia in 1967, Fitzpatrick – by then a grown working artist in Dublin – was moved to create his historic red and black Che poster, one of an original series of different multi-coloured renditions. True to form, the passionate pacifist never thought to copyright his artwork. It was free for all to use, anytime. To Fitzpatrick, it is a work of propaganda and better people accept it as such.

Now, forty-five years later, his 1968 poster is partnered in world history with Korda’s 1960 photograph as one of the most powerful symbols of our times. However, undeniably over the years, the iconic image’s fame has also been bolstered by its unrelenting, unlicensed usage all over the world in consumer product branding, packaging, advertising and much more.

So now Jim Fitzpatrick is “doing the right thing” and gathering and transferring the legal rights to his Che artwork to the people of Cuba, via the Guevara and Korda families. “I had all the legal documentation drawn up pro bono by a lawyer who’s the copyright expert in the whole of Ireland,” Fitzpatrick said. “I would like to see it resolved in such a way that would stop someone else from making vast amounts of money from it. I don’t want to see it disappear off t-shirts, but I do have problems with cigarette companies, condom makers and people like that using the image.

“The Cuban Ambassador to Ireland, Teresita Trujillo is one of my greatest allies in trying to get this thing sorted, and I’ve spent a considerable amount of time with Che’s daughter. For me it’s simply a matter of signing the piece of paper and handing it over. But both the Guevara and Korda families live in Cuba, so you have to be very diplomatic. I promised them I would do nothing until I hear from them, and I’m still waiting. So this could be a long wait.

“The Ambassador gets it, but in Cuba – because of isolation and sanctions – I don’t think they have any idea how important holding the copyright to this image is long term. Trujillo is leaving this country at the end of the year, so I definitely have to get it done. Then I will be able to go to Cuba and hold my up head high, and say I’ve done the right thing.”

Fitzpatrick hopes the legal licensing of his artwork might one day go to help all Cubans. “I would love to see it end up paying for some of the bills in the Cuban medical system. It’s huge and extraordinary and all free, but very expensive.”

On top of the fine artistic skill and passion he brings to all of his artwork – be it his catalogues of Celtic Art, Rock Art album covers or 20-year portfolio of “Mostly Women” – Fitzpatrick is driven by his love for Irish genetics. He is particularly fascinated by the way genetics works, and the way people can misinterpret it.

“I am a six-foot-two, red haired Irishman,” he explained. “My genes are Mesopotamian, so where does the red hair gene come from?” He laughed, “We’re late-comers who arrived around 100 BC, ‘Neo-Celtic’ you know. I recently met Che’s two grand-daughters. One was typically Cuban, with dark hair. The other was light skinned, with red hair and freckles. So you see,” just like Fitzpatrick’s famous poster, “the Irish gene does come back to stir up trouble every now and then.”

Leave a Comment