The Map of Colm Tóibín’s Mind

One of the great successes of Irish fiction writing in the past generation has been the body of work produced by Colm Tóibín. He has greatly contributed to the internationalisation of Irish fiction, setting his novels and stories in countries from Argentina to Spain, while deftly interweaving the political backdrops of those countries with those of our own. He has managed to turn banal subjects such as Henry James’ failed attempts in the dramatic form into lively and fascinating material for a novel, The Master. He has joined the swarms of artists who have tried to depict the holy family in art with something strikingly original in his novel and play, The Testament of Mary. The direction of his work is never predictable: it twists and turns with his instinct to explore new ground.

One of the great successes of Irish fiction writing in the past generation has been the body of work produced by Colm Tóibín. He has greatly contributed to the internationalisation of Irish fiction, setting his novels and stories in countries from Argentina to Spain, while deftly interweaving the political backdrops of those countries with those of our own. He has managed to turn banal subjects such as Henry James’ failed attempts in the dramatic form into lively and fascinating material for a novel, The Master. He has joined the swarms of artists who have tried to depict the holy family in art with something strikingly original in his novel and play, The Testament of Mary. The direction of his work is never predictable: it twists and turns with his instinct to explore new ground.

Then there is the man’s head. On his shoulders sits something that even Pablo Picasso would have envied. Behind his skull is a brain that works in perpetual overdrive and produces a body of work impressive both for its copiousness and originality. His essays, which appear most commonly in The New York Review of Books, give a sense of the breath of his interests and erudition. They pick up where his non-fiction books of the 1980s and 1990s left off in their probing of historically interesting characters, their exploration of gay fiction and Irish identity.

The Irish public’s first encounter with Tóibín was as a columnist and editor of In Dublin and Magill in the 1980s. Those magazines were instrumental in changing the character of Irish journalism, and it was the innovative force of Tóibín, among many others, that achieved it. In an Ireland where homosexuality had yet to be decriminalised, they wrote about gay art; in an Ireland where huge doubt surrounded the country’s Taoiseach’s personal means. This new brand of Irish journalism was packaged in the stylish formatting of the magazines. Magill, by any standards, was very handsomely produced: the exciting voices to which it gave platform were well served by the colourful and provocative presentation of the stories they broke.

Some of the journalistic stories Tóibín wrote—one on ‘The General’, Martin Cahill, another on a judge who was indirectly censored by his colleagues, for example—prompted him to explore in fiction what he had reported on in fact. Tóibín wished to write about what motivated people and what they feared. So Tóibín checked into that great incubator of Irish art, the Tyrone Guthrie Centre in County Monaghan, where he would live for months at a time, pushing himself to produce first class work, emerging only to speak to his close friend, the novelist Sebastian Barry, and to raid the fridge.

Tóibín’s background in journalism enabled him to create cleaner, more authentic fiction than he might have otherwise written. As he put it: ‘Journalism got the poison out of me… I didn’t need to put the anger into novels’. And so his fiction developed apace, and expanded into new territories, such as America. Setting a novel, Brooklyn, in the USA for the first time in 2009 was partly a result of Tóibín’s having lived on and off in American cities for the past ten years. He was appointed to several prestigious visiting positions at Stanford, Texas, Princeton before gaining his sinecure at Columbia University, where he is the inaugural professor of Irish literature. America has been kind to Tóibín, and it was his American-set novel that last year became Tóibín’s first to be produced as a feature film (a US television film was made of The Blackwater Lightship in 2004). Brooklyn tells the story of an Irish country woman transposed to New York during the wave of Irish emigration in the 1950s. The film will premiere next year.

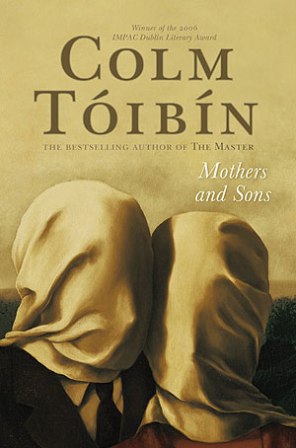

Yet Tóibín’s finest fiction has flourished in his home town of Enniscorthy, County Wexford. Embedded in a series of dark and startling short stories, Mothers and Sons, published in 2006, is a depiction of a middle-aged widow’s emancipation from a dynastic family business that is bringing she and her children to ruin; the story, ‘The Name of the Game’, is an examination in miniature of dozens of orthodoxies of small town Ireland that conspired to sustain the status quo, to stifle the lives of individual talents and to shore up the power of a few families that very cosily carve up power among themselves; the heroine of the story manages, through her own guile and hard work, to break the mould. It is worth recalling that story because Tóibín’s latest work, just published this month, a novel entitled Nora Webster, is also set in Enniscorthy; and like some of his very best work, the novel has as its protagonist a middle-aged determined and forthright woman. Tóibín once said in interview that Enniscorthy is the map of his mind. Its characters live and breathe in his fiction. For all the international plaudits he has received and the experience he has gained, much of the inspiration that has enabled his fiction to reach its potential is attributable to joys and sorrows of his youth in Enniscorthy, and to the characters he met while growing up there. It is there that he has constructed a house that faces out over the Irish Sea and where his mind can fully unfold, and be mapped onto the page.

~ Maurice Fitzpatrick, October 2014

Leave a Comment